Deep Work

This piece is a contribution to the STSC Symposium, a monthly set-theme collaboration between STSC writers. The topic for the upcoming issue is Work.

At the end of a lifetime, an exhausted tylosaurus drifts down to the dusky seabed and takes its rest. A marine reptile consigned to breathe air, it drowns. Dies. Life flourishes around the corpse.

The seafloor that fosters the tylosaur’s final slumber is a sandy plain studded with inoceramids, clams with shells over a meter wide. Small fish navigate the ranks of these giants, picking off nourishment from the oysters and barnacles amassed on top. Many of these bottom feeders find themselves fast gored on the fangs of enchodus, “the saber-toothed herring”, or siphoned into the stomach of gillicus, the pug fish, a two-meter long sucker. It isn’t time at all before the gillicus too becomes feed, gulped up whole by xiphactinus, a close relative built like a fanged tarpon the size of a modern great white. One gillicus manages to struggle in the belly of such a beast, the predatory xiphactinus suffering fatal injuries to its internal organs and likewise sinking to the sands, but this revenge is a rarity, at least as might be encased in fossil stone. The topmost fish are taken by sharks and plesiosaurs—the long-necked elasmosaurids and the speedy, dolphin-like polycotylids—and likewise these hind predators by the peerless king.

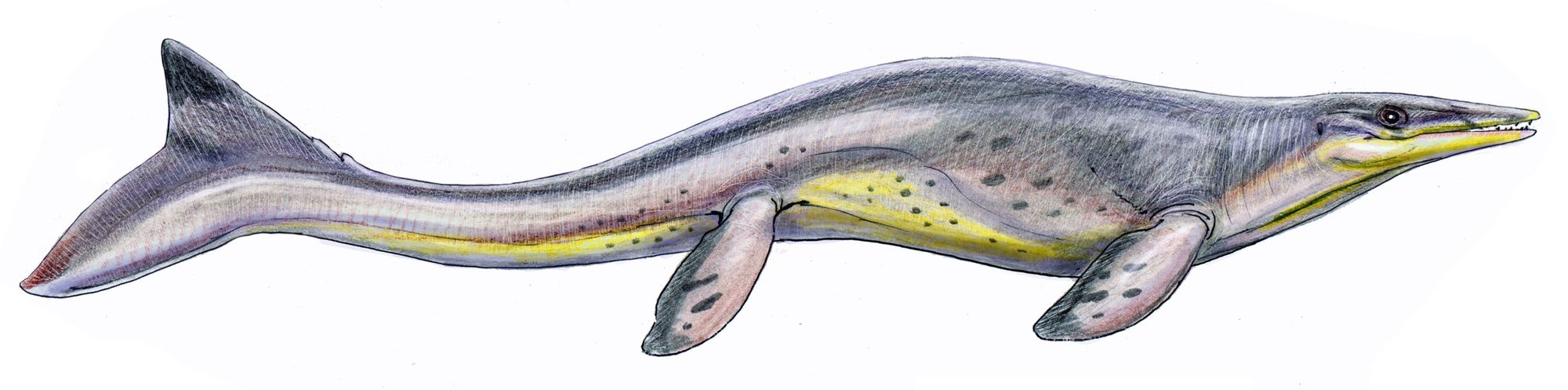

Fifteen meters long and weighing over twelve tons, the tylosaurus rules the food web crackling within the Western Interior Seaway, a wide ocean strip cleaving late-Cretaceous North America down the middle over greenhouse millennia that see the blue planet’s warm waters submerge eighty-five percent of the world. Nowhere in time has there existed a more dangerous setting, the waterways choked with fauna armed to the teeth, caught in the most savage iteration to date of evolution’s conquest. The boiling cauldron of the Western Interior Seaway comes on the heels of a global anoxic event, in which tectonic shifts and volcanism pump the planet with carbon such that algae blooms on the water’s surface. In turn, the algae dies, piles on the sea bottom, and requires all oxygen beneath 130 meters’ deep to begin catabolizing, fossilizing its mass remains. While fish in the photic zone enjoy plant-fueled abundance, all marine life lower than the critical depth suffocates, and so too are doomed the predators who depend on deep life for prey. The Cenomanian-Turonian extinction obliterates twenty-seven percent of marine invertebrates—plankton, ammonites, mollusks, bivalves, more—and up the food chain kills off the reigning apex predators: the last ichthyosaurs, dolphin-shark-tuna fish lizards surviving from the earliest Triassic, and the pliosaurs, whale-sized reptiles with giant flippers and crocodilian jaws. The rising oceans are left in disarray, key predatory niches void, waiting for future fauna to fill them anew. Such becomes the task of ancient mosasaurs ninety-odd million years ago. They are squamates less than a meter long, crawling feebly from land into shallows, but their situation is ideal. From the safety of the shoreline, of waters less than deep, these cousins of snakes and closer cousins of monitor lizards freely adapt and evolve. They quickly radiate into the waiting world’s oceans, the warm, fertile brine of the Seaway. In short order the first tylosaurs, who reach seven or eight meters, crash into the late Turonian, tangle with its worst, and emerge victorious. Tylosaurs and their associates dominate the seas from then on, their reign to be ended only by the catastrophe that blindsided the dinosaurs as well.

The tylosaur newly dead hails from a lineage conceived for carnage. The first seagoing mosasaurs are met by large lamniform sharks, apex predators whose ancestors’ ludicrous versatility has kept them going to this point in the late Cretaceous for 350 million years. These sharks, chief among them cretoxyrhina—the Ginsu shark—are each larger than a great white and just as deadly. They snatch up small mosasaur species and any young that hit the water; mosasaurs give live birth to a few kids at a time, and they mature slowly, their whole lives coming of age in the open ocean. The large sharks are responsible for finishing off the pliosaurs of old, and this time they have the opportunity to nip the mosasaur threat in the bud. But the mosasaurs fight back. Over a few million years, mosasaurs including tylosaurus evolve to both rapidly develop and grow to lengths twice that of the biggest sharks, fattening on the plentiful megafauna: fish, sharks, plesiosaurs, even mosasaurs of different species. From mutual predation builds a war of attrition the upstart mosasaurs win decisively—the extinction of cretoxyrhina tells all. Mosasaurs possess the gamut as apex predators: massive tail flukes to accelerate and ambush fish with higher cruising speeds, a strong set of lungs to hold air and wait on the bottom to take prey above, ear structures modified to amplify sounds and eliminate sensitivity to balance in the marine gyre, nerves in the upper snout to track prey via pressure difference, and a forked tongue to sniff the water in two directions at once. As soon as they grow big enough, only larger mosasaurs are able to stop them tearing through the waves.

Tylosaurus adds to its banner bauplan with adaptations that make it the most gracile and aggressive mosasaur of its mold. Given little time to adjust to marine life, it comes out surprisingly hydrodynamic, much sleeker and more buoyant than other beasts of its length, designed to race and rip. Its snout ends in a robust toothless projection that gifts the “knob lizard” its name. Worn and riddled with bite marks, the tylosaur’s face bears the scars of both ramming prey to stun—later the tactic of choice for megalodon and the sperm whale livyatan when they too strike from below—and fighting others of its kind for territory in a marine ecosystem already flush with giant predators. The tylosaur’s arsenal allows it to feast uncontested on anything it can fit between its gaping jaws, from piscine prey to reptiles, turtles and skimming pterosaurs to toothed sea birds like hesperornis. Even dinosaurs swept out to sea from the halves of the North American continent end up in its craw.

Still, though tylosaurs rule the Seaway for over twenty million years, each individual has a time and plays a part beyond that of the violent feeder. The tylosaur you have already witnessed spent nearly a century moderating its section of the food web, cycling life through its digestive tract, balancing prey populations and the integrity of the ecosystem as a whole. Nature expects her chiefs to maintain her creation, shows all who dare upset things meet a grisly end. A younger tylosaurus once strayed into this one’s territory, ate knowingly, and wound up at the bottom of the sea with its neck snapped, skull crushed. The elder tylosaur served its master dutifully and well, and it was blessed with bountiful waters and lasting life, knowing that in time all spoils come to an end. These too shall pass, as did the tylosaur, serene on the clam-peppered silt basin, which is destined to become the Great Plains in thirty million years, once global temperatures cool, sea levels retreat, and the Western Interior Seaway disappears in the last. Only now does the savagery of the Seaway consume the tylosaur, just as the top predator itself partook of the teeming broth. Within minutes of expiration, two gray squalicorax, the crow sharks, stooges and cleanup for cretoxyrhina who have somehow survived their late master, sweep in to scavenge the tylosaur’s remains. Other animals will soon follow, sea urchins and brittle stars bringing up the rear. Around them the giant clams flutter, awestruck, scattering the small bottom feeders and their predators above them. An easygoing archelon, at almost five meters the largest turtle in history, passes overhead with its own piscine escort, barnacles and algae for the troop’s sustenance growing on the turtle’s shell.

The turtle waves, the clams flutter again, and the crow sharks continue to gorge. A shoal of toothy pachyrhizodus pursues smaller fish across the water column, stubborn xiphactinus in tow, and a six-meter bonnerichthys vacuums plankton at the surface, to attract any number of predators seeking its own meaty vessel. Below, a giant squid lurks, hides. All is right with the Seaway. In death, the tylosaur gives the squalicorax an opportunity to do their part, and so too other scavengers, decomposers, the nitrogen cycle, life anew. Each animal, each form a sublime punctuation of nature’s flow, is geared for something unique and true. The apex predator performed its task admirably, suffered voluminous daily hunting and reaped the rewards with utmost grace, and finally it gives the last of the life it accumulated back to the Seaway, such that the waters ripple and shiver and shine even in their deepest hues.

By design, to each his work, to each her calling.

So, what’s yours?

Member discussion